Why ask for Open Access

Professor Anna Kristina Hultgren (@akhultgren, 2022)

I write this post in hindsight to share why and how I am trying to publish what I can open access. I realise that academic Open Access (OA) publishing comes with commercial strings attached and that it is not impervious to its own conflicts of interest and iniquities (the money to publish OA comes from somewhere: open access may be free to read but it’s definitely not free to do!). Despite its own commercial self-interests, I think it democratises knowledge more than the paywalled alternatives.

What is Open Access publishing?

Open Access academic publishing is shorthand for describing digital texts (such as books and journal articles) that are free to read, download and share without breaching copyright. Within the context of academia, OA is becoming increasingly possible for at least the following reasons:

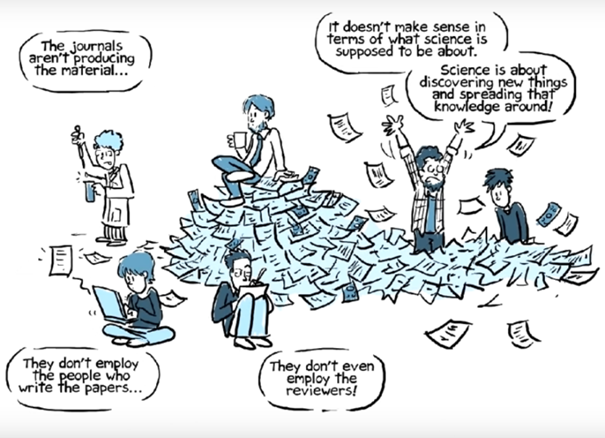

- Traditional paywalled academic publishers have been rumbled. They are billion-dollar profit-making businesses that rely on the free labour of academic writers and reviewers. They make their money by having exorbitant licence fees which universities are obliged to pay so their students and academics can access them. Universities are therefore paying twice to make their own research available: they pay their academics salaries so they can publish research in the first place; and they then subscribe to those same journals so they can read their own work.

- Whilst publishers clearly incur costs for marketing, distributing, maintaining websites, etc., the business model of academic publishing is increasingly being seen as unethical because it profits from free labour, it charges readers for accessing knowledge that has already been paid for by tax-payers and student fees, it doesn’t pay its authors to write for them and it excludes the many who can’t afford to buy this knowledge (not to mention that some academic publishers are also investing these profits unethically)[1].

- Sci-Hub has been hosting pirated copies of scientific papers for a long time and because authors are generally happy to share their work when approached directly, paywalled research is actually quite easy to by-pass, thus becoming potentially redundant.

- There are now several companies which act as open access ‘brokers’, paying publishers up-front to publish research monographs by crowdfunding from university libraries.

Why I opted for Open Access

The short answer is that I write for free and would like to be read for free, too. The longer answer has to do with democratising and pluralising knowledge by ensuring everyone in the world with access to the internet can read research, regardless of whether they have the money to do so.

When I say I write ‘for free’ I mean this literally. I don’t get paid by the publishers who contract me to write and I am a part-time academic. For the past 10 years, I have also been on teaching-only contracts with no obligation to research or publish (although I now have a research post). The tacit expectation to publish, however, has always been there since I can’t teach what I teach without contributing to its scholarship. So, de facto, my research and my writing have happened during non-paid time. Back in 2020, when I first approached Bloomsbury Academic Publishers with a book proposal based on my PhD research, I asked them what chance the book had to be Open Access, and here is what I learnt.

How Open Access works

Publishing open access is expensive business: about £2000 for a journal article and about £8000 for a research monograph (a book). These costs compensate the publisher for (some) lost paywalled revenue and they are either paid by the author or their institution or some other funder.

But it also works in more subtle, indirect ways. Commercial gains are still being had by publishers with open access portfolios. As the Pay Wall film explains, universities (via their libraries) and publishers are keen to be ‘perceived’ to be socially just (possibly more than they are keen to actually be socially just), and for this reason, they are willing to pay for some of their research to be freely available. There is pressure on both to commit to as much open access as possible in order to be ‘seen to be’ democratic and fair and therefore not alienate new generations of ‘customers’ who are concerned about socially just academic practices.

Yet, when I approached my university 2 years ago asking whether they would consider footing the open access bill for my book, I received a convoluted response that referred to ‘gold and green routes’ and more acronyms than I care to comprehend.

The answer was essentially ‘no’. My only other option, at the time, was to either pay the £8000 (impossible) or crowdsource the amount, but that was unrealistic given the time scales and the fact that my research is not important enough to warrant the generosity of strangers.

Then something significant happened. My Commissioning Editor at Bloomsbury took the lead and nominated the book for selection by Knowledge Unlatched, an open access brokering company (which, btw, has since been purchased by Wiley) that paid Bloomsbury what it needed to ensure the title could be published open access and widely marketed (what’s in it for Knowledge Unlatched, you may well wonder? Well, apart from their mission to make knowledge freely available, they also receive money from university libraries who pay them in return for cheaper licencing).

But I think that what also helped me make the case for Open Access in the first place was the content of the book and the endorsements of 2 eminent scholars who are committed to socially-just literacy practices (Professor Chrissie Boughey and Professor Suresh Canagarajah, who wrote the foreword and the afterword, respectively).

Committing to socially just academic writing practices

Being able to do what I preach matters enormously to me. Like many others, I suffer the injustices, promises, constraints and contradictions of working in the capitalist regimes of the Global North academy. These regimes are ideologically committed to charging people who want to be educated, privileging those who can pay at the expense of those who can’t, all the while bolstering a higher education business model that is premised on precarious employment, increasing student fees and unfair working conditions. As Canagarajah argues

Professor Suresh Canagarajah (@sureshcanax)

I am therefore grateful that, via Bloomsbury, I have had the opportunity to contribute to the ‘process of dismantling unequal structures’ by at least ensuring that those who want to can read what I think for free.

This post has benefitted from the insightful and generous feedback given during a Writing Circle session with post-graduate research students at the Open University’s Graduate School (@OUGradSch). Thank you everyone!

Sources

- ‘Towards a philosophy of academic publishing’ http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2016.1240987

- https://paywallthemovie.com/

- https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/explainers/what-open-access

- https://www.bloomsburycollections.com/open-access/

- https://sites.psu.edu/publishing/blog/is-peer-review-biased-locating-inequality-in-global-academic-publishing-in-the-neoliberal-system/

- https://www.bloomsburycollections.com/book/what-makes-writing-academic-rethinking-theory-for-practice/afterword

- https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-022-00556-y

- https://knowledgeunlatched.org/ku-crowdfunding/

- https://helenkara.com/2018/05/01/how-open-is-open-access/

- https://globallabourcolumn.org/2022/03/02/uk-university-strikessecurity-equality-and-a-decent-life-after-work/

[1] https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/feb/24/elsevier-publishing-climate-science-fossil-fuels