Defining knowledge

I begin 2020 with one of several reflections on ‘knowledge’, an age-old concept the meaning of which is being disfigured by ill-intentioned and disingenuous leaders, most notably during the highly toxic and xenophobic UK-US political discourses of 2019 and debates on the climate crisis.

Inevitably, ‘western’ academia is concurrently being forced to question its own ontological and epistemological grip on reality.

I need to keep up with these debates, mainly because my research is on academic writing and how it claims to ‘shape knowledge‘, but also because I am increasingly identifying philosophies of higher education, values and social justice as fertile sites for making sense of the epistemic crisis. These sites seem to hold the shifts in perspective and language needed to make sense of epistemic toxicity and self-doubt.

Knowledge and true belief

Knowledge is a concept that is slippery and hard to define. A very flawed but intuitive definition consists of understanding it as follows:

“There is a way things are that is independent of us and our beliefs about it” (Boghossian, Fear of knowledge, p. 3, 2006).

This is hugely problematic, yet frequently invoked by default across all disciplines and in every day life (arguments with teenagers notably spring to mind here – it’s not my opinion, it’s a fact!).

Papineau (2019) claims that a better way of thinking about knowledge is in terms of being ‘open to a fact’ because, presumably, this gets rid of the trouble we run into when we invoke the notion of ‘things being independent of us’ (but he then argues against this position on the grounds I outline below). This way of thinking about knowledge, i.e. being ‘open to a fact’, is based on lines of sight: agents are assumed to know about what lies in their direction of gaze when nothing is in the way. This discriminatory ability can provide a foundation for the concept of knowledge. Those who have this ability can divide agents into those who know some fact and those who are ignorant of it. Basically, I can be said to ‘know something’ if I can see it clearly.

One of several problems with this understanding of ‘knowledge’ is that it doesn’t distinguish it from ‘having a true belief’ about something. For example, by believing ‘that I can see something clearly’, I get the same result as knowing ‘that I can see it’. By eliding the difference between ‘knowing’ and ‘believing’, Papineau concludes that we may as well do away with the concept of ‘knowledge’ and replace it with the concept of ‘true belief’.

‘Belief’, however, is a mental state that requires a ‘self’ (i.e. someone has to be believing), so knowledge in this sense of ‘belief’ can’t be ‘independent’ of us, either. This still doesn’t rule out the possibility of the external world being independent of us (in a Kantian sense), but it does mean that our knowledge of/belief about this world depends on us. This indicates that facts can be defined ontologically (i.e. we can say there is an objective/real world that is independent of us) as well as epistemically (i.e. in terms of how we come to know the world, including the normative value systems that we use to describe it).

Knowledge of this world can, therefore, only ever be our knowledge. It is not ‘knowledge’ that is independent of us. In this sense, knowledge can only be epistemic, not ontological, because it requires a ‘self’ to orient how we come to know the ontology.

Knowledge is mediated by the ‘self’

The history of science and philosophy have highlighted that the ‘self’, including its technologies (Foucault), mediates between us and the external world. Kant famously posited that the world appears to us as it is because of the subjective categories of space and time that we project on to it. Hume, Nietzsche, Wittgenstein and Foucault also questioned what it means for things to be ‘independent’ of us.

Thinking of knowledge as ‘things that are independent’ of us is, therefore, untenable (and I hereby pledge to stand by this claim, even whilst arguing with my teenager).

Knowledge as ‘epistemic virtue or vice’

Once we accept that knowledge of the world involves knowledge of our ‘selves’ or of a ‘belief’ about how things are, we begin to notice that, rather than facts, it is a series of values (virtues and vices) that underlie the way we talk about the world. In other words, we pass judgements on the ‘way things are’ and are actually unable to talk about these ‘things’ as if they were ‘independent’ of us.

When we talk about the world being ‘real’ or ‘true’ or ‘objective’ or ‘relative’ or ‘just’ or ‘diverse’ or ‘structured’ or ‘stratified’, etc., we are judging it to be one way or the other, we are never describing it ‘as it is’.

Daston and Galison (2007) provide a fascinating historical perspective of epistemic virtues, of how ‘objectivity’, ‘truth’, ‘idealisation’, ‘pedagogic communicability’, ‘certainty’, ‘precision’, ‘replicability’ are human values rather than facts about the world. They show how these epistemic virtues and vices have played different roles at different times in shaping the Western concept of knowledge. They also show how virtues morph into vices as a result of human judgment, not facts.

The tension between self (including its technologies and extensions) and object are at the heart of the epistemic virtue lens.

The history of knowledge highlights diverse epistemic virtues (EVs), which I list below. These do not replace each other but evolve into each other. From truth-to-nature approaches that reify general idealised types; to mechanical objectivity that reifies individual objects devoid of relations and structures; to relational invariants that try to communicate structural objectivity; and then family resemblances that can only be detected via trained judgment.

The book traces 3 epistemic virtues (EVs):

- Truth-to-nature (pre 1800s), when artists and scientists worked together to depict an idealised/sanitised/selective paradigm of nature/reality.

Artists and scientists worked together with ‘four eyes’ to capture the ‘essence’ of nature, drawing it but also stylising and sanitising it for pedagogic purposes and selecting what features were considered typical of a species and airbrushing out anomalies. Tensions sometimes arose between how the artist saw the object and how the scientist saw it.

Truth-to-nature was a ‘self-centred’ epistemic virtue, not an ‘objective’ one.

- Mechanical and structural objectivity (18-1900s), when the ‘self’ was eliminated. This project failed, even though it still lingers in how we think about science.

Machine-mediation gave the impression that objects could be seen ‘as they were’ with no mediation of the self, no airbrushing of anomalies. Sight was now considered a vice, not a virtue, and the virtues of denial and restraint of the self became paramount for science (from ‘four-eyes’ to ‘blind eyes’).

But mechanical objectivity posed several problems, one being that it depicted objects in a way that was now ‘too real’ and therefore difficult to communicate pedagogically. What could be seen under a microscope or how structures were related, (eg snowflakes), now needed interpretation. A ‘scientific self’ was needed to mediate between the world and how it could be communicated.

This ‘scientific self’ manifested several virtues. He [sic] was patient, persevering, slow, methodical, reasonable and diligent. Newton is an example.

But this self was still too interfering in mediating reality. He was not objective. Nature needed to be ventriloquised (ie separated from the self). But this still required a ventriloquising ‘self’, namley someone to speak on behalf of nature.

Structural objectivity was invoked as the way to continue eliminating the self and to ensure that knowledge of the world could be communicated unequivocally and universally (cf analytic philosophy and the Vienna Circle). According to analytic philosophers and mathematicians, eg Frege, ‘objective is the law-like, the conceptual, the judgeable, what can be expressed in words’ (p. 267).

Clearly, however, this, too, was a subjective stance since only a ‘self’ can do the ‘judging’.

Structural objectivity failed, as did the analytic philosopher’s project because the world is substantial (cf Toulmin) as well as structural. Biology is a science of substances and properties (eg blood, colour, flesh, organic matter, environments) as well as structural relations (eg physics).

- Trained judgment (1900s and beyond), where the self is needed to make sense of (judge and interpret) reality.

The expert and trained judgments of the scientist bring the ‘self’ back into play to make sense of ‘family resemblances’ between objects, not ideal types. The need to classify, manipulate, interpret patterns, graphs, electroencephalograms, etc. requires a ‘self’.

Concluding reflections

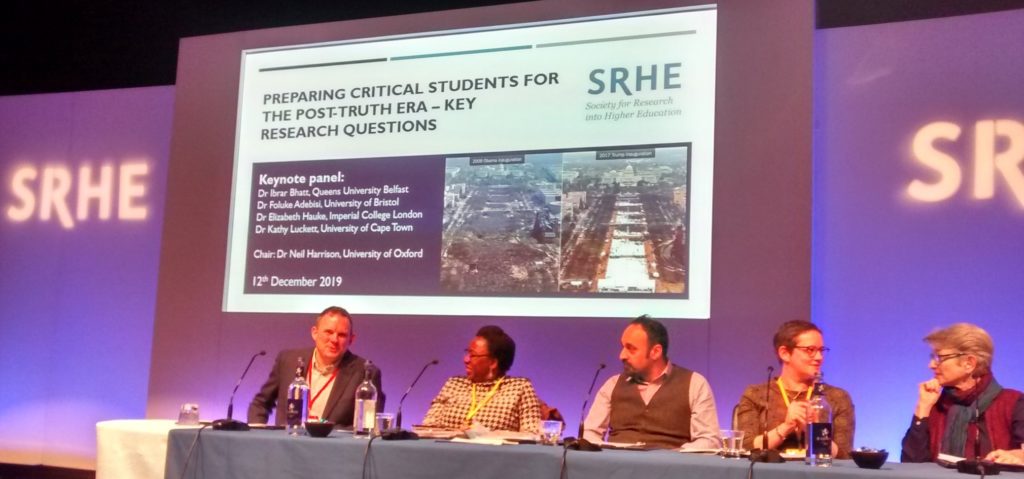

The post-truth era requires a Self that is trained to judge and is transparent about their values. This does not make them infallibe ‘experts’, but it does make them more qualified and informed than others to make judgments that are concurrently explicit about the values that orient that judgment. When judgments are trained and values are explicit, others can, in turn, make their own equally trained judgments in accordance with their values.

So, what might today’s epistemic virtues look like? What virtues and vices underscore the key epistemologies of this century’s humanism: post-humanism, Big Data, post-truth, ecologies of knowledge, climate change, gender, standpoint theories?

What role does the ‘self’ play and what responsibilities does it have in today’s educational landscape?

How can we reclaim confidence in knowledge without transcending into irreality, hubris and vice?

And, crucially for me, what role do academic writings have in shaping epistemic virtues and vices?